Introduction

Museums and other cultural landmarks are becoming increasingly significant actors in landscape making processes, recognized by UNESCO ever since 1972, safeguarding municipal regeneration or the urbanization at a vast territorial scale.[1] Researchers have valued the phenomenon as a “Paradigm Shift” (Nikolić, 2012) regarding art “as urban defibrillator” (Mantziou, 2019). Constructing, as they say in French, “imag(inair)es sur le territoire” (Hottin, 2024), is shaping museum provision all over the world with such political emphasis that the power of image even prevails over that of collection care (Bishop, 2021). Museums in the “Bilbao era” become proud icons of the city and the cultural district into which they are erected (Lorente, 2025). Thus, museums are no longer isolated containers of collections, but rather the dispersed nodes within the infrastructure network, where the urban “effect” is expected be multiplied when a city multiplies museums and other art installations.

Fostering “cultural tourism”, many museums are built or under construction, restored or renovated – the “museum boom” that started during the mid of 1970s, gaining momentum during the 1980s, 1990s throughout Europe and other continents, has reached full blow in China at the beginning of 21st century. The spatial configuration of museums[2] is becoming one of the criteria to evaluate the degree of modernization nowadays. The concept of “cluster” in Economics, as “a concentration of specialized industries in particular localities” (Marshall, 1890), has been in practice for a long time in manufacturing industry, in cultural industries is expected to lead a similar positive impact in China, where the term “museum cluster” emerged in early 21st-century policy documents, at first in urban planning and later in cultural and tourism.

Yangzhou provides a critical sample in this dynamic, with a dozen of museums and other amenities concentrated on the urban map. Yet is this already a cluster, or still at an incipient phase that should instead be considered as an agglomeration? This article examines this question on the light of current practices in Yangzhou.

1. Numerous museums in a cultural heritage site.

Recent milestones —including the World Heritage designation of the Grand Canal, the opening of both public and private museums, and the excavation of significant archaeological sites— are giving regained visibility to Yangzhou, a historic city renowned for its private gardens, religious monuments, urban districts, traditional crafts, and performing arts. As a convergence point of both tangible and intangible heritage, this city presents a comprehensive context for understanding the functions and current situation of museums in-situ.

Since the excavation of the Han Canal (邗沟) and the founding of Han City (邗城) by King Fuchai of Wu (吴国) in 486 BCE, the city has had more than 2,500 years of recorded history. It gained remarkable prosperity under several dynasties —including the Han (汉), Sui (隋), Tang (唐), and the prosperous Kangxi–Qianlong (康乾) period of the Qing (清) — and consequently developed into an epicentre of regional cultural production, nurturing intellectual and artistic groups such as the Yangzhou School (扬州学派), the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou (扬州八怪), and the skills of lacquerware, jade carving, Penjing (盆景), woodblock printing, and Huaiyang cuisine. In recognition of its outstanding historical and cultural value, Yangzhou was included in the list of National Historic and Cultural Cities by the State Council in 1982. The heritage of Yangzhou includes both tangible and intangible categories.

For the tangible heritage, within the property of the Grand Canal World Heritage Site, Yangzhou contains six designated heritage sections and ten component sites: Liubao sluice, Yucheng post station, Shaobo ancient embankment, Shaobo wharf, Slender West Lake, Tianning Temple (including Chongning Temple), Bamboo Garden, Salt Merchants’ Residence of Wang and Lu, and the Guild Temple of Salt. The six waterway sections include the Ancient Han Canal, Gaoyou and Shaobo sections of the Ming–Qing Canal, the Inner Canal, the Ancient Yangzhou Canal, and the Guazhou Canal.[3]

Its intangible heritage covers different aspects of daily life, for instance, Guqin art (2003), traditional woodblock printing techniques (2009), paper-cutting (2009)[4], and the craft of Fuchun tea pastries (2022) are inscribed on “Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity” of UNESCO. In addition to the international registration, Yangzhou also preserves 20 national-recognised intangible heritage.[5]

Museum development in Yangzhou dates to the early 1950s, right after the foundation of new China in 1949, when the Northern Jiangsu Province Administrative Office established the Yangzhou Cultural Relics Museum at Shrine of Shi Kefa.[6] In 1953, this institution was renamed as “Yangzhou Museum”, but its visibility in public’s daily life was very limited during nearly half a century. The crucial change happened in 2003, when the State Council approved the creation of the Yangzhou Chinese Block Printing Museum in the premises of Yangzhou Museum, thereby forming a “Double Museum” complex, open to the public two years later.[7] In this integration, 300,000 woodblocks for book-printing collected by the Guangling Publishing House were transferred to Yangzhou Museum.

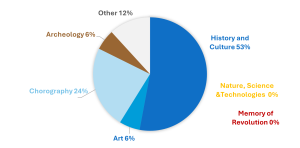

By 2021 there are in total 17 state-owned registered museums in Yangzhou,[8] including Yangzhou Museum, the Longqiuzhuang Prehistorical Archaeology Site Museum (龙虬庄遗址博物馆), the Tang Dynasty City Ruins Museum (唐城遗址), the Han Dynasty King Guangling Mausoleum Museum (汉广陵王墓), the Cui Zhiyuan Memorial Hall (崔致远纪念馆), the China Grand Canal Museum (扬州中国大运河博物馆), and several sub-administrational county museums. By 2022, all of Yangzhou’s museums are state-owned. Among them, 14 are under the cultural relics system, while 3 belong to other sectors. In terms of subject matter, historical and cultural museums form the largest proportion (52.94%). Yangzhou’s museums comprise nine historical –cultural institutions, one art museum, four comprehensive or local history museums, one archaeological site museum, and two classified as “other.”[9] There are no natural, science and technology or Revolution memorial museums. In addition, the Yangzhou Intangible Cultural Heritage Treasure Exhibition Hall and the Sui Emperor’s Mausoleum Museum were built and open to the public by 2024. (Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Proportion of museum types in Yangzhou in 2022, data source: «Jiangsu Province 2022 Museum Development Report» drawn by Ling Jingyuan

Figure 1. Proportion of museum types in Yangzhou in 2022, data source: «Jiangsu Province 2022 Museum Development Report» drawn by Ling Jingyuan

| Museum Name | Location | Heritage-related | Type |

| China Grand Canal Museum | Municipal District | Yes | WH |

| Yangzhou Museum | Municipal District | ||

| China Block Printing Museum | Municipal District | Yes | ICH |

| Memorial Hall of the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou | Municipal District | ||

| Memorial Hall of Shi Kefa | Municipal District | Yes | National |

| Former Residence of Zhu Ziqing | Municipal District | Yes | Provincial |

| Yangzhou Buddhist Culture Museum | Municipal District | ||

| Yangzhou Penjing Art Museum | Municipal District | ||

| Hangji town Toothbrush Museum | Municipal District | ||

| Tang Dynasty City Ruins Museum | Municipal District | Yes | National |

| Memorial Hall of Cui Zhiyuan | Municipal District | ||

| Han Dynasty Guangling King Mausoleum Museum | Municipal District | Yes | National |

| Jiangdu City Museum | Municipal District | ||

| Baoying City Museum | Baoying County | ||

| Study Residence of Zhou Enlai | Baoying County | ||

| Yizheng City Museum | Yizheng County | Yes | Provincial |

| Gaoyou Postal Relay Museum | Gaoyou County | Yes | WH/National |

| Gaoyou City Museum | Gaoyou County | Yes | Provincial |

| Gaoyou Philatelist Museum | Gaoyou County | ||

| Longqiu Zhuang Prehistoric Archaeological Site | Gaoyou County | Yes | National |

Table 1. Source: Statistical data of Jiangsu Provincial Department of Culture and Tourism,

Directory of Museums in Jiangsu Province, 2024

Museums in Yangzhou perform multiple functions. First of all is the basic function of collection and preservation.[10] They provide physical environment that shelter those cultural objects. Meanwhile, these museums are increasingly getting to strategic positions within regional and global networks. They cooperate with professional associations, non-governmental organizations, and international partners to address contemporary issues.

In 2023, the Annual Conference of CMA Museology Committee reunited Chinese museum professionals and scholars from metropoles and provinces to discuss museum issues in the Grand Canal Museum. This institution brings Yangzhou city in global discourse: its permanent exhibition, “World-Famous Canals and Canal Cities,” aligns with the Grand Canal Museum Alliance and the objectives of the World Historic and Cultural Canal Cities Cooperation Organization (WCCO). Beyond the preservation and safeguarding of cultural items this museum is expected to play a role in cultural diplomacy, following the international tendency in times of globalization. [11] The Marco Polo Memorial Hall, established under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the National Cultural Heritage Administration of China and upgraded in 2021 with support of the Italian Consulate General in Shanghai, and with participation of University of Venice, demonstrate how museum can bring communities together and fostering a deeper understanding of diverse cultural heritages, thus, social cohesion.

Beyond heritage preservation and networking, museums in Yangzhou also play a vital role in the local economy. Since the opening of the Yangzhou Grand Canal Museum to the public, the city’s tourism sector has experienced a boost—a remarkable phenomenon in China. This museum-led dynamic has further stimulated the creative economy through the development of cultural and creative industries, such as products derived from museum collections, intellectual property licensing, and heritage-based urban programme such as the Yangzhou Intangible Cultural Heritage Industrial Park, which generates employment opportunities and contributes to regional development.

2. National cultural policy vs local implementation.

Favourable policies both relevant to territorial development strategies and cultural heritage provide museums in Yangzhou opportunities. The inscription of the Yangzhou section of the Huaiyang Canal as part of the Grand Canal World Heritage is meaningful. After the inscription, there has been a boost of tourism contributed by the in-bund tourists, particularly those from vicinage provinces which bring thus a considerable income to local finance. Subsequent initiatives—such as the Outline for the Conservation of the Grand Canal Culture and the Regulations on the Protection of the Cultural Heritage of the Yangzhou Section of the Grand Canal—have provided a framework for heritage preservation and museum development. Provincial ambitions to make Yangzhou a “World Capital of Canal Culture” further reinforce this direction.

A series of national policy documents issued between 2015 and 2020, such as the Regulations on Museums, Guiding Opinions of the State Council on Strengthening Cultural Relics Work, and the 13th Five-Year Plan for the Development of Cultural Relics have established strong legal and administrative foundations for museum growth. Complementary local measures, including the Regulations on Promoting Tourism in Yangzhou and the Implementation Opinions on Promoting the Integration of Culture and Tourism Industries (2021–2023), have guided the practical implementation of these frameworks. Yangzhou’s location at the intersection of multiple strategic zones, such as the Belt and Road Initiative, Yangtze River Economic Belt, and Grand Canal Cultural Belt provides exceptional connectivity and policy synergy. Internally, the city benefits from rich intangible cultural heritage resources, traditional craftsmanship clusters, and emerging cultural parks, forming a solid basis for museum innovation. Digital transformation also offers new momentum. National initiatives —such as the National Cultural Heritage Administration’s online exhibition platform (2019) and the Guidelines for the Digitization and Cataloguing of Intangible Cultural Heritage Resources, issued by the National Center for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, China Academy of Arts (2023)— have accelerated the adoption of virtual tools, which could provide guidance to Yangzhou’s digital transformation in museum sectors. However, alongside these opportunities, Yangzhou’s museums also face a range of challenges that may hinder sustainable and inclusive growth.

In ideal theories on paper, the paradigm of “Concept → Policy → Action” are often filtered with romantic colour, but in real practice, particularly in sub-administrative areas, the situation is more complex. Following the “museum boom”, a “polarization” is observed in the museum landscape in China: while major museums are breaking records both in terms of collection and visitor numbers, many small and medium-sized museums in the regions are being lagged. Most museums in Yangzhou fall into this latter category. The China Grand Canal Museum is becoming one of the country’s top ten most visited museums, but it is also a particular case because it is administrated by Nanjing Museum Institute – a provincial level institution. Other museums in Yangzhou, administrated by the municipality or the sub-administrative counties, have yet to find effective synergies, leaving the goal of “large and small museums developing in collaboration”[12] unfulfilled. In the urban centre, the overconcentration of museums has already resulted in problems of parking and traffic congestion. In contrast, the suburban and peripheral areas remain underserved.

With the accelerating transformation of cultural heritage sector at the national level, the local museum administration system remains underdeveloped. In terms of grading, some museums lack clear identification and positioning, which hinders their access to funding and acquisition. Among the registered state-owned museums, more than half are identified as “history and culture”, followed by “local chorography”, with archaeological site and art museums underrepresented. When it comes to the city’s history, Yangzhou Museum do have a gallery on the 3rd floor titled of the city’s ancient appellation, however, in consideration to the city’s 2500 years history, the museography of this permanent exhibition appears more like a “welcome hall” of a luxury hotel with artificial decoration but with little objects exhibited. The immense museum space is not sufficiently serving its cultural aims. In other cases, similar problem persists: curation projects emphasize their form over substance, interpretation is with admirable tone but without informative content. When it comes to the relevance of heritage sites, the current content does not align with the city’s recognized World Heritage and nationally listed intangible cultural heritage, thus failing to fully convey Yangzhou’s Outstanding Universal Value (OUV). When visitors come in order to discover Yangzhou’s city history and culture, they can be disappointed by the homogeneous content, very similar to what is present in museums of Hangzhou, another city along the Grand Canal. Furthermore, the absence of dedicated archives related to heritage constrain public access to museum/heritage research.

Besides, museums in Yangzhou encounter several operational difficulties. A staff member from a local township office of cultural and tourism explained: “Local investment is insufficient, and little effort is made to seek financial support from superior level of authority. This leaves local museums and small memorial halls struggling for survival.”[13] Some newly build exhibition halls, owned and run by enterprises, do possess adequate collections and are collaborating with curatorial agencies, however, due to their ambiguous institutional status, they are somewhat excluded in official activities, even if their museography looks in some cases more professional than that of a certain big museum. And even more worrying, right after the installation, their innovations could be copied and pasted to one of the galleries in a big public museum, but without any remuneration. This lack of protection of intellectual property discouraged their motivation of innovative practices. Digitization also presents challenges. Many projects are outsourced to agencies with skills in digital tools but without expertise in history, archaeology or museology, which results in inaccurate interpretation. Those initiatives are frequently set up to fulfil “digital transformation” directives from higher authorities, the missions may have been accomplished formally, but the demand of public for access to information are very often overlooked. Consequently, such digital facilities do not always advance the goal of “inclusivity”, sometimes, on the contrary, are becoming the barriers that lead to “exclusion”.

3. Public art in museums’ outdoor spaces within heritage precincts.

The installation of public art has been particularly visible in Sanwan Park where the Grand Canal Museum is located, as well as in the Longqiu Zhuang Prehistoric Archaeological Site (龙虬庄遗址). Both sites take advantage of their immense occupation of land to make the installation possible, but by different means and with different purpose. Other surrounding museums hardly present any public art because of space limitations. Museums dedicated to notable historical figures often place group statues or bronze busts at their entrances to commemorate these individuals, being faithful to the existing portraits in archives without much artistic creativity.

Sanwan park’s art installations present iconic and textual interpretation. At the east gate of the Sanwan Park, the first feature that comes into view is a wooden, mountain-shaped screen wall composed of vertical wooden sticks, the inscription of the park’s name“大运河国家文化公园–运河三湾景区”. The sides of the screen wall are adorned with a series of openwork shallow reliefs depicting Yangzhou’s classical gardens and ancient poetry. (cover image) Behind this screen wall, to the right, a grey upright cube is installed at a 45° angle. One of its faces displays the golden logo of the Grand Canal National Cultural Park along with its name in both Chinese and English, while another face features the UNESCO World Heritage emblem and a map of the Chinese Grand Canal showing the cities it passes through. The river channels and city names are rendered in gold and raised in relief, standing out prominently from the flat surface. (Figure 2.)

Sanwan Park envelops both the Grand Canal and the Grand Canal Museum. This spatial proximity permits the extension of the museum architectural, with a continuation of the canal heritage display. However, in the real practice, with a considerable quantity of land occupation, this park is more like a natural park than a relevant museum and heritage institution. Public art works in this park are limited as isolated markers, rather than components of a symbol system that mediates pathways, nodes, and memory points, that guide visitors’ movement with heritage interpretive cues resonating with the museum’s internal narratives. The generic representations of the city’s historic figures on some of the public art installation even diminishes the heritage coherence.

Figure 2 Cube with World Heritage emblem and Grand Canal map

photo by Jingyuan Ling, 2025

At the Longqiu Zhuang Prehistoric Archaeological Site, public art installations adopt a more figurative approach. One piece features a dark stone stele incised with eight symbol-like marks. The column on the left resembles oracle bone script, while the one on the right evokes animal-shaped motifs. According to the label at the lower right, these pictographic symbols were derived from a pottery sherd —specifically, the rim of a burnished black earthenware basin excavated at the site. However, the absence of any image of the original artifact leaves visitors confused and creates a sense of disconnection from the underlying collection. Another installation consists of three blocks of marble: two cubic elements forming a supporting base and a circular slab set between them, its surface engraved with a circular knot motif. The label identifies the work as “China’s Number One Knot,” explaining that it was inspired by a pottery spinning wheel unearthed in 1993, which bears an interlocking design symbolizing cyclical continuity. Yet the reason for calling it “number one” remains unclear—whether it refers to the earliest known knot excavated in China or simply the largest example. As with the stone stele featuring the oracle-like inscriptions, there is no explicit link provided between the public artwork and the archaeological objects. (Figure 3.)

It appears that this local institution tends to use public art installations to compensate for weaknesses in its collections—a museum housed in a cabane with few exhibited objects, because the excavated artifacts were transferred to the Nanjing Museum, the provincial capital, by the excavators in the 1990s. However, the incomplete and scientifically insufficient information provided on the accompanying labels leads these installations to create a confusing experience for visitors.

Figure 3. “China’s Number one Knot,” inspired by a pottery spinning wheel unearthed at Longqiu Zhuang Prehistoric Archaeological Site in 1993, bearing an interlocking pattern, symbolizing cyclical continuity, Photo by Jingyuan Ling, 2024

Public art in Yangzhou’s heritage settings reveals a gap between the initiatives and the result: the presence of artworks is noticeable, yet their capacity to shape cultural meaning and spatial experience remains underdeveloped. The park and the site provide adequate space for artistic intervention, but the installations often function as isolated visual marks. Across the museums landscape in Yangzhou, public artworks tend to adopt literal approaches, but rarely move toward more curatorial, narrative-driven, or conceptually grounded expressions – serve for the heritage authenticity. As a result, the outdoor spaces lack a coherent artistic language capable of complementing or extending the museums’ thematic narration. Instead of guiding movement, leading views, or mediating between architecture and landscape, the works generally serve decorative roles. The greater challenge lies in the absence of a unified curatorial strategy that could connect the artworks with the historical, archaeological, and environmental contexts they are intended to evoke.

Conclusion

How successful is the combination of public art, museums and other heritage landmarks in Yangzhou? A key point to be highlighted is the significant distinction between “cluster” and “agglomeration”. While agglomeration refers to the “geographical concentration” [14] of facilities or buildings within a given area, a cluster implies infrastructures with a deeper level of interconnection at both spatial and institutional level. The construction of a package of museums in a city does not automatically form a cluster, which is something more: conjoint synergy[15]. In this context, the efforts of several museums to extend their presence in their surrounding outdoor spaces through the installation of public art represent early attempts to build a more immersive cultural panorama. These interventions have yet to function as lines that connect narratives across sites or reinforce shared heritage identities. For museum agglomeration to evolve into a museum cluster, a more strategic plan is necessary at local level that could foster the cooperation among institutions and public art could move beyond stand-alone marks but operate as an integrated spatial and interpretive medium.

[1] 1972 World Heritage Convention, UNESCO, https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/

[2] Note from author, see Jingyuan Ling’s speech at “Making Cultural Infrastructure in Non-Metropolitan Areas more Inclusive” in session 4A Infrastructure, service delivery, governance, in digital transformation for smart, sustainable cities, 12th Annual International Conference on Sustainable Development (ICSD), New York, 2024.

[3] The Grand Canal, World Heritage, UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1443

[4] Yangzhou Paper-Cutting – China Intangible Cultural Heritage Network · China Intangible Cultural Heritage Digital Museum, https://www.ihchina.cn/project_details/20180.html

[5] Jiangsu Provincial Department of Culture and Tourism, 2023, http://wlt.jiangsu.gov.cn/art/2023/10/23/art_695_11049618.html

[6] Note of the author: Shi Kefa (1601–1645) — Military commander under the Southern Ming. Revered as a national hero for his defence of Yangzhou City and his martyrdom after the city’s fall to Qing forces. The Shrine of Shi Kefa was built by Qing government.

[7] Charter of the Yangzhou Museum, https://www.yzmuseum.com/html/Page/list/70.html

[8] The Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development of Yangzhou 2022, http://www.yangzhou.gov.cn/yangzhou/gmjj/202303/7cf5b0068ca244cb9926174d6f1191b2.shtml

[9] 2022 Jiangsu Museum Development Report, published in 2023

[10] In reference to the ICOM Museum Definition, updated in 2022, https://icom.museum/en/resources/standards-guidelines/museum-definition/, consulted in 2024

[11] Note from the author, “The Evolving and Transformative Role of Museums: Beyond Preservation and Safeguarding of Cultural Heritage”, one of the panel sessions of the High-Level Forum for Museums, Hangzhou, People’s Republic of China, 23- 25 April 2025

[12] Proposed by CMA (ICOM China) Museology Committee in 2021

[13] Interview with a staff in Cultural and Tourism Bureau of Daqiao town, Jiangsu Province, 2023

[14] Note from author, definition of “Museum Cluster” on Academia: “A museum cluster refers to a geographic concentration of museums that collaborate or share resources, enhancing cultural tourism, educational outreach, and community engagement. This concept emphasizes the interconnectedness of institutions to promote collective visibility and accessibility of cultural heritage.” https://www.academia.edu/Documents/in/Museum_Cluster

[15] Evaluation of UNESCO’S Museums Programme, UNESCO, 2025. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000395199.locale=en