I: Early imitation and critique after the 19th century

In 1840 the last feudal dynasty of China, the Qing Dynasty, went to war with Britain, a war that opened the doors to closed trade and shattered a cultural environment that had been closed for thousands of years in this part of the world. The backward, agrarian country was vulnerable to the industrialized British army, and so were culture and the arts. The Qing government reluctantly embraced European science and art, and in order to continue the rule of the empire, the powers-that-be attempted a top-down revolution, starting with new education and reforms in the fields of science, culture, art, and medicine, thus sending for the first time government-organized teams of foreign students to European countries to study and record their experiences. Since then, the introduction of Western culture never stopped until after the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912, and Picasso’s works came to China with Chinese and European merchants, scholars and colonizers after that.

In 1915, Mr. Cai Yuanpei, a famous educator in modern China, heard that Picasso had settled in Paris after arriving in France and went to visit him on his own initiative. Mr. Cai Yuanpei bought at least five Picasso’s works, which were the earliest Picasso’s authentic works flowing into China, marking the official introduction of Picasso’s works in the country. Cai Yuanpei commented on Picasso’s painting that «at first glance, it looks like a pattern, not a pattern; it looks like a figure, not a figure», and «to see a thing and realize that its beauty is nothing but the feeling of all kinds of lines» (apud Wang, 2010)[1] . This is also one of the earliest records of Chinese scholars’ evaluation of Picasso’s paintings. This kind of works, which were different from traditional Chinese art, had aroused great discussion at that time. Although mainstream Chinese art had always emphasized meaning over realism, as Cai Yuanpei said, Picasso’s works seemed to be plausible and indistinguishable from the effects presented by traditional Chinese art at that time: at first scholars of polygraphy thought that Picasso’s work was a kind of fantasy or a vague expression of dream. Many art scholars thought so, as the Chinese art field at that time had not experienced the iteration from the Renaissance to Expressionism and Cubism. However, Cubist paintings appeared at first beyond the understanding of the Chinese, for lack of theoretical knowledge. This situation was not improved until scholars studied and published relevant academic reports in the following years, and gradually became one of the important models for Chinese artists and scholars to study and refer to in the subsequent development.

In 1917, Jiang Danshu mentioned «Cubism» in his History of Art handbook published in Shanghai by Commercial Press: a brief textbook for Normal Schools and one of the earliest works on art history in China. Cubism was just succinctly defined: «The study of the volume of an object, in order to express the sense of volume on the screen». In 1918, Kang Dan-Shu edited and published his Reference Book of Art History as a supplementary reading material. This book explained important Chinese and foreign painters’ schools and terminologies in the form of word descriptions and new contents were added under the directory of «Cubism», mentioning Picasso as the leader of one of the schools of painting recently started in Paris, which advocated to rebel against the focus of Impressionism on motion, light and color in order to express the volume of objects in paintings. This is one of the earliest comments on Picasso in Chinese writings, establishing the fame of Picasso as the main founder of Cubism.

In his History of Western Art published in 1922, Mr. Lui began to introduce other representatives of Cubism in detail, but Pablo Picasso remained the leading character, describing him as someone curious by nature, who had imitated the works of various artists at first, but surpassed their influence immediately, especially when he saw the carvings of the natives in Feizhou, which were mostly made of simple cubic shapes, changing his painting method by using various geometrical shapes in order to seek the reality of nature.[2] Lui based his work on the English translation of French scholar Salomon Reinach Apollo : histoire générale des arts plastiques, although that initial edition of that book only covers the 19th century. [3] But Lui drew on a variety of other works to update the history of European art, stating in the pages on Picasso that he was inspired by the art of black Africans to create Cubism.

After Lu’s 1918 reference book on Western Art History, Chinese publications on the general history of Western art followed the convention of placing Picasso under the name of Cubism. In 1929, Liang Deshuo compiled and published in 1929 an Outline of Western Art, based on William Orpen’s Outline of Art, which had been published in 1924 and contained more than 300 illustrations, 24 of which were printed in color. Liang Dexao, who presided over the Liangyou Book Printing Company, exerted his advantage in publishing, and all the plates were printed on coated paper, and 10 color plates were selected for printing, which were extremely well-made, and probably one of the most luxurious art history books in the Republic of China period. The book illustrations include three works of Picasso, the most highly treated artist in the book, whose chapter 21 introduced «Late Impressionism, Cubism and Futurism» where Picasso continued to be listed as the inventor of Cubism (Liang, 1929: chapter 21).

Most of the general histories of Western art published in the early Republic of China were compilations of works by European or Japanese scholars, and the narrative framework of these works, which put Picasso into Cubism, limited the initial understanding of Picasso in China. Accordingly, Picasso’s works more frequently included were those of the Cubist period. As Picasso’s status in the European art world increased and his style continued to evolve, this situation gradually changed.

Western art history books published after the 1930s began to divide Picasso’s art style into more detailed categories, discussing the differences between Picasso’s pre-Cubist and post-Cubist phases. In 1936 Liu Haisu adapted and published The Modern Movement in Painting, by British scholar T. W. Earp, distinguishing several stages in Picasso’s career before Cubism: the «Cyan Age», «Naked Age» and the stage of paintings influenced by black art (Liu, 1936). Then Picasso’s «Cyan Era», «Pink Era», «Cubism Era» and «Neoclassical Era» were mentioned by Ni Yide in his 1937 Explanation of Western Schools of Paintings (Ni, 1937).

At the same time, local Chinese artists did not always praise Picasso, but also criticized him. Xu Beihong, as an advocate of realism in Chinese art, wrote an article in 1933, calling Picasso’s Cubism «a formal game that destroys the laws of modeling», believing that it deviated from the social responsibility of art, and bluntly said, «I would rather take the realism of Courbet than the deformation of Picasso. In his 1943 Review and Prospect of the New Art Movement, he wrote: «European modernist paintings are capable of deformation and abstraction, which is really a way out from nature and claptrap.» He categorized Picasso’s Cubism as a typical example of Formalism, considering it contrary to the purpose of art serving the people (Xu, 1943). This view was not uncommon in Chinese art at system the time, as realism was more popular in the early days of contact between traditional Chinese painting and Western art. During the two decades of the Republican government after the fall of the Qing dynasty, Chinese scholars and artists gradually became closer in their knowledge of the development of world art and its trends. Thanks to the Republican government’s lax control over culture and academia, there was no obstacle to academic development at the time. Western books were widely circulated and used in China’s early university education, which enabled Picasso to establish his identity not only as a founding master of Cubism and Abstraction, but as a pioneer and mentor of modern art worldwide, including the Republic of China. The ideal of the great master is pivotal in Chinese culture, rooted in jianghu culture and the respect of Confucianism for referential teachers. Picasso’s status as a patriarch in the field of modern art was assumed by Chinese art leaders who would boldly imitate Picasso’s style. For example, the promoters in Shanghai of the Jilan Society, founded in 1931 and active until 1935 when it was dissolved. Most of its members were young artists who had studied in Europe and advocated breaking the boundaries of traditional art, introducing Western modernist techniques, and creating new styles. In 1931, theorist Ni Yide, the intellectual leader of the Society as well as a professional contributor, issued a manifesto calling for the Chinese art world to break free from all shackles to create independent and free Chinese art. Following his advice, the members of the Society created a number of new works that combined Western modern art styles.

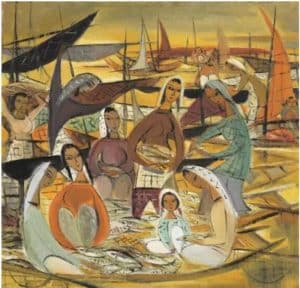

Above all painter Eileen Pang (1906-1985), who was the founder and core leader of the Juelan Society. In his early years, he studied in Paris, France, where he came into contact with Cubism and decorative arts and then, returning to China, devoted himself to the fusion of Chinese and Western arts often combining ethnic decorative elements with geometric abstraction explicitly inspired by Picasso’s works: e.g. his 1932 watercolor on paper So Paris (lost in 1937), which expresses the modern image of the urban woman with mechanical forms. He organized four exhibitions of the Duelan Society and drafted a manifesto, proposing to «create art for a new era with the same passion as a raging torrent». Dedicated to the promotion of arts and crafts education, he later became the president of the Central Academy of Arts and Crafts, influencing the development of modern design in China experimenting with mixed media, combining collage, metal sheets and traditional craftsmanship.

Another pioneer in the creation of the Jue Lan Society, was Zhang Xian (1901-1936). With a background of studying in France, he was closely associated with the pioneering modern artists in Paris, and was a great admirer of Picasso, whose influence can be seen in his short but very experimental artistic career. For example, his 1932 oil painting Figures (Collection of Liu Haisu Art Museum) uses hard-edged lines to divide the picture, fuses Cubism and Primitivism, borrowing from African sculpture, and simplifies the human body into geometrical blocks. He exhibited his most modern works at the Jurassic Society exhibition, but his untimely death prevented further explorations.

Other fellows of artists’ groups could also be cited. Yang Yang (1907-2009) was a young member of the Guangxi School of Painting. His art style tended to be abstract, and his 1934 watercolor Dance of the Universe expressed dynamics with abstract lines, and later turned to watercolor painting, blending with oriental moods. Zhang Qin (1901-1936) studied in France in the 1920s and was a core member of the Duelist Society, briefly active in Shanghai’s modern art scene. In the 1930s Zhang’s figures were painted with contrasting color blocks contoured by thick black hard-edged lines inspired by Picasso, imitating his Mademoiselles d’Avignon with angular faces and limbs geometrically shaped. He also drew on Picasso’s references to African masks for his 1933 Dancer, whose face shows exaggerated eyes and simplified features, with the roughness of primitive art.

Chang Yu (1901-1966), who signed Sanyu, lived in Paris for a long time, from the 1920s to the 1960s, being close to Picasso in the Montparnasse art circle. The balance of curves and planes in Sanyu’s Nude Woman, an ink and wash on paper dating from the 1920s, combines with a background divided into space by flat color blocks, echoing Picasso’s combination of the Rose Period and Cubism. In Vase and Chrysanthemum an oil on fiberboard from the 1940s, he simplified the pot and flowers into geometrical outlines with strong color contrasts, which is close to Picasso’s still lives. Although Changyu’s style is more inclined to Fauvism and Expressionism, his exploration of form remained faithful to Picasso’s resonance.

Four art exhibitions were conducted from 1932 to 1935 by pioneering artists of the Jurassic Society, creating a considerable wave in the Chinese art world at that time, and more artists embarked on this path. For example, Lin Fengmian (1900-1991), who studied in France in 1919-1925 and was the principal of Hangzhou National College of Fine Arts, advocating the harmonization of Chinese and Western art. Influenced by Picasso’s use of geometric composition and color segmentation, Lin Fengmian’s paintings of opera characters and still lives follow the geometric block segmentation of Cubism, for example, the faces and dresses of the opera characters in his series «The Lotus Lanterns», started in the 1940s, are simplified into sharp-edged geometric blocks of color, while the background is made of interlocking lines to create a sense of spatial deconstruction. Fusion of multiple perspectives, collaging boats and houses at different angles, could be the main feature in the series “The Fishing Village” from the 1940s onwards, borrowing the Cubist compositions of superimposed multiple points of view, while retaining the fluidity of the ink rendering. When teaching in Chongqing in the 1940s, he said to his students: «Picasso broke the shackles of perspective, but the scattered perspective of Oriental art is a thousand years ahead of him. His innovations are worth studying, but there is no need to worship them.»[4] Lin Fengmian did not directly imitate Picasso, but integrated the deconstructive thinking of Cubism into the tradition of Chinese painting, forming a unique style of «Modern Orientalism». In many ways, Picasso was the common teacher of early Chinese modern art painters, who dialectically viewed and absorbed his advanced concepts and combined them with local elements to create a new style of Chinese art.

II: Around 1949 to the 1970s

After Mao Zedong’s assumption of power within the Chinese Communist Party and the establishment after 1935 of a provisional communist government in Yan’an, Shaanxi Province, China, Picasso became a referential figure as he was politically engaged and deeply responsive to international changes. In 1944 the French newspaper L’Humanité published the world-shattering news that Picasso had announced that he was joining the French Communist Party. When the news reached Yan’an, Jiefang Daily published an article «Celebrating the French painter Picasso’s joining the Communist Party»[5] . On February 4rd, 1945, Xinhua Daily also published Picasso’s article «Why I joined the Communist Party». On May 5th of the same year, Xinhua Daily again reported further news: «The Great Painter Picasso Goes to the Front to Sketch»[6] . At this time China was divided: after Japan surrendered and withdrew from China, there were two armies on Chinese soil, belonging to the Communist Party and the Kuomintang respectively. The Communist Party was deeply influenced and financed by the Soviet Union while the Kuomintang sought more assistance from the United States, thus gradually a military confrontation between the capitalist and the socialist camps was formed in China. Picasso was then celebrated in socialist countries all over the world, and it was an excellent opportunity for the Communist Party of China (CPC), which was ostensibly in a weaker position at that time, to publicize the news, which was interpreted by the Party’s media and newspapers as a strengthening of the Comintern and a cultural victory for the socialist camp, especially because such an artist who had occupied the status of a great master in the field of art appeared to make the Communist Party more widely popular.

Mao Zedong, then Chairman of the Communist Party of China, took a personal interest on this matter. In 1945, he had an exhibition organized honoring Picasso, the only foreign artist who had an exhibition in Yan’an at that time; but the exhibits were all copies from photographs, because of the limitations of the government of Yan’an.[7] No image remain as historical testimony and the event was not boosted longtime, as Picasso soon distanced himself politically from communist orthodoxy. Nevertheless, this exhibition had a direct outcome: Picasso painted a portrait of Mao Zedong as a gift to him. In September 1945, Picasso entrusted Deng Fa, a representative of the CPC who was going to Paris to attend the World Congress of the Federation of Trade Unions, to bring his portrait of Mao Zedong to express his admiration for the legendary Yan’an. Li Pei, the wife of Guo Yonghuai, the founder of the «Two Bombs and One Star», who knew about the event because she represented Chinese women at that time, said, «Picasso asked Deng Fa to bring a painting to Chairman Mao, and Deng Fa even held the painting for me to look at it.» Regrettably, when Deng Fa was returning to China, on April 8th, 1946, with Wang Ruofei, Qin Bangxian, and others in an American transport plane, the aircraft crashed: all the 17 people on board died and Picasso’s precious paintings disappeared from then on. There was a long controversy about this «natural disaster» allegedly due to bad climate, as many suspected a man-made conspiracy.[8] Indeed, according to the memoirs of Du Jitang, an agent of the military intelligence, the incident was an action planned by the military intelligence to sabotage political changes.[9]

Whatever the case, after a brief period of friendship, political influences were gradually brewing, and with the initial end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949 and the founding of a new China under the leadership of the Communist Party of China (CPC), the nascent nation initially adopted the patterns of the Soviet Union in politics and in cultural life, which led to the rapid disappearance of various modern innovations that had begun to emerge in the early 19th century. As a result, China’s mainstream aesthetics and art forms became homogenized, mimicking the socialist realism of the Soviet Union: new China’s requirements for art were simple and rough, the style must be popular and easily accepted by the public, the content must be in line with socialist values, and the ultimate purpose must be to serve the people or propagate the socialist ideology, under such an environment, foreign modern artists were gradually ignored. Picasso in particular became increasingly questioned in the party, convinced that his belief in socialism was not strong enough. For example, after the death of Stalin in 1953, communists all over the world actively mourned him. Picasso, commissioned by the Comintern, produced a charcoal sketch of a young Stalin, with lively lines which dissatisfied the party leaders, who criticized the lack of solemnity or grief. But Picasso himself did not think that there was anything wrong with his portrait and refused to correct it.[10] Then, although Picasso remained a member of the party he was gradually labeled as being noncompliant and individualistically bourgeois. This accusation was fatal and directly led to the rapid fading of his artworks and style from the public eye in China. A huge portrait of Stalin was placed in Tiananmen Square China lowering the flag at half-mast for three days and placing, calling on the whole country to lay flowers whereas different provinces organized relevant processions, which showed how much importance the Chinese authorities attached to his iconic figure –but not according to Picasso’s iconography.

As China’s early socialist construction progressed, the political issue of oppression in the field of culture and the arts intensified, and the struggle over the socialist line continued to expand after 1950 as internal conflicts within the Party intensified. The so called Cultural Revolution started in 1966 when Mao Zedong, the chairman of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC), became under the influence of the Gang of Four: his wife Jiang Qing, followed by Zhang Chunqiao, Yao Wenyuan, and Wang Hongwen promoted to the CPC Central Committee from Shanghai and entrusted with important responsibilities.[11] During the ten years all walks of life in Chinese society were dominated by political struggle, and political tendency became the first element, while the cultural and artistic fields, which were already restricted, were devastated. The restrictions on art were horrifying, and Picasso’s works, which had already been sidelined and faded out of the public’s sight, were laughed as bourgeois art during this decade, and accused of being seriously harmful to the construction of socialism. Artists and related groups took it upon themselves to criticize this type of art in order to prove themselves politically faithful. Even Einstein’s theory of relativity was defined as bourgeois science, thus it is not surprising that subjective literature and modern art became suspicious.

Foreign art exhibitions simply became extinct during this period.[12] All artworks were done by collective creative groups, generally with a fixed ideological pattern to express the glorifying themes of the times. Local revolutionary committees prescribed the contents and ideas for National art exhibitions, proudly closed to foreign artists. In May 1972, the Cultural Affairs Section of the State Council organized the «National Exhibition of Works of Art in Commemoration of the Thirtieth Anniversary of Chairman Mao’s Speech at the Yan’an Literary and Artistic Symposium», which received high attention from the revolutionary committees of the various regions, which set up the corresponding offices of the art exhibitions. According to Gao Miande, the main organizer, more than 2,000 works displayed in the four national art exhibitions were selected from the 12,800 works recommended by various regions and troops. During four years, a total of more than 7.8 million visitors were received, far more than any national art exhibitions before the Cultural Revolution.[13]

After the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, the artistic literacy of the whole society had retreated to the levels of the 19th century and China was once again ignorant of the modern art of the outside world. After the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, Hua Guofeng, Ye Jianying and other leaders took decisive measures to put the Gang of Four under quarantine, ending the control of the country by their extreme left. In August 1977, the 11th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) formally declared the end of the Cultural Revolution. Nevertheless, its consequences remained, as a large number of intellectuals were persecuted, including many literary figures and artists, which led to the stagnation of the cultural and artistic fields in China, especially regarding foreign art, which was totally ignored by the general public.

III: 1980 to 2000

When Deng Xiaoping assumed power, he focused on economic development and made the decision to repair relations with the Western world, actively participating in the process of globalization. The policy of internal reforms and opening up to the outside world that China implemented after the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in December 1978 was aimed at emancipating the productive forces, introducing the market economy and promoting modernization. Scholars gradually began to resume their academic work and set out to improve and repair the gaps in Chinese art. A cultural milestone was the 1980 book, A History of Modern Western Art, with a special chapter to Picasso, regarded as «a revolutionary who broke the traditional conception of space».[14] However, not all scholars would leave Marxist inertia. For example, Li Zehou, in his 1980s lectures and subsequent books warns Chinese artist not to follow him, stating that Picasso’s «formalist revolution» reflects the alienation of capitalist society.[15]

With the Chinese government’s active action in foreign affairs, the most significant exhibition of foreign artists after the founding of China was finally held in 1983, on the occasion of a state visit by French President Mitterrand.[16] Drawing on Picasso’s popularity and the antecedents celebrating his art in China, the French government at that time joined hands with the Chinese Ministry of Culture to promote a show of Picasso’s authentic works. On the French side, Dominique Bozo, director of the Picasso Museum in Paris, led the selection process, focusing on the versatility of Picasso’s artistic language and avoiding overly politicized works. China set up a special working group responsible for customs clearance, assuring security as well as temperature and humidity control at the exhibition hall. At that time, China had no experience in introducing Western artworks on a large scale, thus French experts guided the entire exhibition.[17] From May 6 to June 5, 1983, the National Art Museum of China in Beijing held a grand Picasso exhibition. A total of 33 oil paintings, 7 prints, 3 sculptures and 36 ceramics were displayed, totaling 79 original works, covering all stages of Picasso’s career from 1901 to 1971.

The exhibition was a sensation in Beijing, causing great repercussions and becoming the largest foreign exchange activity after the Cultural Revolution. The average daily number of visitors exceeded 5,000, and the total number of visitors exceeded 100,000, setting a record for a single exhibition in the National Art Museum of China. However, due to the social environment at that time, some visitors were confused because they could not understand Picasso’s style, and comments such as «it looks like children’s paintings» appeared in the guestbook. Tickets for this exhibition were designed as individual commemorative coupons and were collected by art enthusiasts, doubling their price on the black market at one point.

The Picasso exhibition was a successful piece of cultural diplomacy and is seen as a watershed moment in China’s acceptance of Western modern art. Previously, China had only sporadically introduced Impressionism, and the appearance of Picasso as a benchmark figure of modernism in this exhibition marked the beginning of official recognition of avant-garde art, a change of attitude that allowed the Chinese art field to break free from its past constraints. Institutions such as the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) organized group viewings for teachers and students, sparking discussions on formal innovation. Later renowned artists such as Chen Danqing and Luo Zhongli, for example, recalled how the exhibition inspired them to break out of their realistic frameworks. Fine Arts magazine opened a column to debate «form and content» and «the politics of art», where some scholars criticized the exhibition for «promoting Western decadent art», but many more commented positively the exhibition, recognizing its pioneering value and saying that it was a new type of art worth studying.[18] Jean Clair, a French art historian, pointed out that the curatorial strategy of the exhibition intentionally downplayed Picasso’s communist identity and highlighted his image as a «pure artist» to meet China’s cultural demand for «de-ideologization» at the time. This narrative strategy enabled the exhibition to pass through the political censorship, but it also triggered criticism from a post-colonial perspective that it covered up the political resistance in Picasso’s art. The exhibition was not only an artistic event, but also a micro-mirror of China’s social transformation during the early period of reform and opening up, and its complex historical repercussions are still being reinterpreted by art history researchers. The operational experience of this exhibition (e.g. insurance, international transportation, copyright agreement) laid the foundation for the subsequent introduction of exhibitions of Western masters such as Gauguin and Dalí, etc. After the 1990s, the National Art Museum of China gradually formed a regular international loan mechanism.

On the other hand, the 1983 Picasso Art Exhibition had a great impact on many Chinese artists, inspiring the New Wave Art Movement, a storm of artistic innovation that spread across the country in 1985. About 120 spontaneous art groups emerged between 1985 and 1989, forming regional schools: Northern Rational Painting by the Northern Art Group (Shu Qun and Wang Guangyi) advocated the aesthetics of the sublime, and their work The Absolute Principle used geometric compositions as a metaphor for order. Jiangsu and Zhejiang Lifestream by Nanjing Red Brigade (Ding Fang, Shen Qin) explored suffering and redemption with expressionist brushstrokes, with their masterpiece The Power of Tragedy. Southwest New Figurative by Mao Xuhui and Zhang Xiaogang explored the subconscious and individual experience through the Private Space series. Xiamen Dada by Huang Yongping burns the History of Chinese Painting, subverting and deconstructing the authority of art with Zen and Duchampian style.

Picasso became an important object of study again in this art innovation movement, which was roughly divided into four directions. First, the technical revelation of deconstructing the realistic tradition, Picasso’s Cubism broke the rules of single perspective, which directly impacted the realistic system of Chinese academy school. This inspired the «85 New Wave» artists to make breakthroughs in formal language: Wang Guangyi used cold geometry to reconstruct the human body in Solidified Polar North, combining Cubism with the minimalist aesthetics of the north. Mao Xuhui’s Red Human Body painted in 1984 expresses mental anxiety through distortion, implying a mix of Expressionism and Cubism. Second: the catalyst of media experimentation, Picasso’s ceramics, collage and other cross-border creations exhibited in 1983 expanded the boundaries of art media and pushed the «85 New Wave» artists to break away from easel paintings: Xu Bing’s Heavenly Scripts questioned the authority of language by using pseudo-script installations, continuing Picasso’s reconstruction of the symbolic system. In Red Humor, Wu Shanzhuan appropriated political slogans and made collages, similar to Picasso’s deconstructive strategy of integrating newspaper fragments into the picture. Third: the awakening of the consciousness of ideological enlightenment and modernity, and the declaration of artistic independence. Picasso’s refusal to attach himself to any ideological artistic stance inspired the «85 New Wave» artists to pursue the ontological value of art. For example, Shu Qun’s Absolute Principle explores metaphysical order through purely geometric compositions, attempting to strip art of its social functionality. Zhang Peili’s 30× 30 uses video to record meaningless movements, echoing Picasso’s creative concept of «art needs no explanation». Including the awakening of individual consciousness, the strong personal style of Picasso’s works stimulated Chinese artists to shift from collective narratives to individual experiences: Zhang Xiaogang’s The Love of Life explores family memories through surreal dreamscapes, which forms a cross-temporal dialogue with Picasso’s metaphors of individual traumas. Gu Wenda’s ink experiments deconstruct traditional culture with words, alluding to Picasso’s «destructive borrowing» of African sculpture.

Although learning and borrowing were the mainstream reactions, controversy and reflection on Picasso’s works became also an important part of this innovative movement. Some of the «85 New Wave» artists were wary of simple imitation of Western modernism: Huang Yong Ping considered Picasso as a «patriarchal symbol that needs to be transcended», and his artwork literally deconstructed the authority of Western art history, including Picasso.[19] Xu Bing proposed that «the real avant-garde should start from local problems», and his performance Ghosts Hitting the Wall, in which he printed the Great Wall, attempted to find an oriental methodology other than Picasso’s dismantling of traditional rules. The «85 New Wave» was essentially a creative misinterpretation and transformation of Western modernism. This dialogue across time and space not only embodies the anxiety and desire of Chinese art in the early stage of globalization, but also reveals the complex tension between borrowing and resistance of local avant-garde art. As Chinese art critic Gao Minglu said, «Picasso is a mirror that illuminates the self-reconstruction of Chinese artists in their pursuit of modernity».[20] This booming art scene allowed the Chinese market to respond quickly to the reform and opening up of China, and private art museums and galleries appeared in this part of the country. The founding of the Shanghai Art Museum (now the China Fine Arts Palace) in 1991 signaled the emergence of private art exhibitions and collections, and paved the way for the explosion of Picasso’s art exhibitions in China after the year 2000.

III: Chinese reception of Picasso in the 21st Century

After the economic reforms integrating China to a market economy, the country has gradually opened up, also in cultural matters. Now educated Chinese people are most familiar with Western art masters, especially 19th-century European artists and the pioneers and leaders of modern avantgardes have been introduced to Chinese people in textbooks and popular handbooks. For example, Notes on Modern Art by Fan Jingzhong, published in 1999, includes historical information on Picasso’s interactions with Chinese artists such as Zhang Daqian, and analyzes his interest in traditional Chinese art and its two-way cultural influence. Wu Guanzhong’s Quotations on Paintings, released in 2000, refers to Picasso several times, believing that his «metamorphosis from realism to abstraction» confirms the universal value of «formal beauty» and describes himself as being inspired by his colors and structures in his creations. Demystifying Picasso, an audio-lecture by Wang Duanting, examines in detail Picasso’s borrowing of Chinese calligraphy and bronze motifs and analyzes his influence on painters of Chinese descent such as Zao Wou-ki and Chu Teh-chun.[21] In 2014, Five Hundred Years of Chinese Oil Painting by Zhao Li and Yu Ding, the third volume «Modern Transformation», uses Picasso as an example to discuss how Chinese oil painters such as Wu Guanzhong and Zao Wou-ki have reconstructed the local aesthetics by means of the language of Cubism (Li & Yu, 2014). In 2015 Zhang Xiaogang’s oil on paper Amnesia and Memory, painted in 2001, recalls that when he was at the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts in the 1980s, he broke through the boundaries of realism by copying Picasso’s albums, with a particular focus on the symbolic and tragic expressions in Guernica. The Theory of Intentionalism and the History of Contemporary Chinese Art analyzes the connection between Picasso’s primitivism and China’s Vernacular Art Movement of the 1980s from a global perspective, emphasizing misinterpretation and innovation in cross-cultural borrowing (Gao, 2009: see esp. Chapter 1: Abstraction is the core product of Western modernism). Many more examples testify that Picasso enjoys a strong presence in Chinese art bibliography nowadays, boosted as well by the art institutional scene.

In 1999 the Chinese government introduced the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Donations to Public Welfare Utilities, providing a legal basis for private museums to accept donations with tax incentives. Thus, China’s museums are booming, amounting by 2023 to more than 4,500 state-owned institutions, whereas the number of private museums exceeds 2,000.[22] In order to quickly gain popularity in the same type of competition, as well as to secure revenue and relevant state subsidy payments, these museums have chosen to organize exhibitions of famous art masters. In this new era, numerous individual theme exhibitions have become important benchmarks in the public reception of Picasso’s art in China.

A momentous breakthrough was the 2011 China-Picasso Exhibition organized by Shanghai Tianxie Culture Development Co., Ltd. with an investment of RMB 50 million, while the venue and hardware facilities were provided by the China Pavilion of Shanghai World Expo Park. The collections came all from the Picasso Museum in Paris, then closed for refurbishment. A total of 62 Picasso masterpieces were displayed, with a total value of about 678 million euros. The whole exhibition lasted for more than 80 days from October 18, 2011 to January 10, 2012, displaying Picasso’s complete artistic career from the «Blue Period» to his later years in chronological order, supplemented by 50 photographs recording his life. The exhibition attracted more than 300,000 visitors, with a daily average flow of about 3,700 people, making it one of the cultural events in Shanghai that year. The exhibition received high social attention and extensive media coverage, and was regarded as the first heavyweight cultural feast after the Shanghai World Expo. In terms of influence and cultural popularization, the exhibition was the first systematic presentation of Picasso’s art in its entirety and his largest solo show in Asia. At the same time, this exhibition is also an industry benchmark, as a private enterprise-led international exhibition, exploring the operation mode of cultural projects supported by non-government funds and accumulating experience. Through this exhibition, Picasso’s popularity rocketed again.[23]

Where popular interest is massive, some people want to take profit. Indeed, the Picasso Comes to China exhibition arranged by Beijing’s Shanshui Wenyuan Group in 2015 was an iniquitous example of pure business. Public expectations were very high as, according to the promotional materials of the organizer, there would be 83 pieces of Picasso’s authentic works from 8 collectors in 5 countries, covering Picasso’s entire creative cycle from youth to his later years, including oil paintings, prints, drawings, manuscripts, engravings, ceramics, and including 84 photographs. A huge investment in media publicity from the beginning of April 2015 to the opening on May 28, mobilized hundreds of media rounds throughout the country, Beijing TV, CCTV as well as the Global Time, etc. In addition, the organizer also invited movie stars and TV hosts, and also invited the Counselor of the Italian Embassy in China and the Ambassador of Spain in China to attend the opening ceremony, where the deputy director of the National Museum of China made a speech… A marketing strategy of this scale instantly attracted countless enthusiastic viewers, and the network program at that time jokingly claimed that half of Beijing city was here. But questioning voices appeared. Many were disappointed by the number and quality of the contents. The number of paintings was scarce, just five pictures on loan from private collections. Their quality was also questionable, especially in the case of Two Nude Men, dated 1897, a very ordinary oil on canvas, 80.6X64.4cm, with no signature, perhaps an unfinished draft painted when Picasso practiced with the nude at the age of 16, but some experts doubted its authenticity, as it was unknown in previous studies about Picasso. As for the other four paintings, they were not a great lot either: Portrait of Tilda, a 1902 charcoal drawing; Bust of a Woman, an oil on canvas from 1954; Flowers, a 1958 gouache on cardboard; The Musketeers oil on canvas dated 1964. The latter seemed quite problematic: just an unfinished draft with only simple lines and a few blocks of color, making the style of the painting quite different from the Musketeers that have appeared at auction. No specific information was given on precedence and about the owners of this paintings, everything was very vague. Next, there were 36 prints: 15 from the Studio d’Arte Contemporanea di Guastalla (Italy) and 21 from the art company Pesaro (Italy). Of the 36 prints, just 11 were signed and numbered, 10 were signed but unmarked and 15 were both unsigned and unregistered. The rest were 5 rectangular ceramic plates and 35 pieces of pottery, all on loan from an art gallery in Pesaro (Italy) and the Guastalla Studio of Contemporary Art in Milan (Italy). No museum or academic institution was involved, it all seemed a deceiving business and, whereas China’s per capita income in 2015 was far lower than that of Europe, where the entrance fee for the Picasso Museum in Paris was then the equivalent of 91 yuan and that of the Picasso Museum in Barcelona corresponded to 80 yuan, this Beijing Picasso Art Exhibition charged 120 yuan, making many people feel cheated.[24]

In addition to ticketed and profitable exhibitions, some important commercial companies have also used Picasso to expand the popularity of their activities. For example, on October 15, 2016, Christie’s unveiled its new location in Beijing and held an opening ceremony for the Picasso Special Exhibition, which celebrated the Spaniards’ 250th anniversary worldwide. At the same time, the special exhibition «Picasso’s Muses and Myths» was held as the first exhibition in the new space, focusing on Picasso’s representative works from different periods of creation for Beijing collectors and art lovers. At the same time, works by pioneering masters from the East and the West, including Max Ernst, Fernando Botero, Chang Yu, Chu Teh-Chun, and Zeng Fanzhi, are also on display. The event was attended by Mr. Kenneth Peng, Global President of Christie’s, Mr. Wang Zhongjun, Chairman of Huayi Brothers Media Company Limited, Mr. Duan Yong, Director of the Department of Museums and Social Heritage of the State Administration of Cultural Heritage of China, Mr. Wei Wei, President of Christie’s Asia, Mr. Gao Yilong, Chairman of Christie’s Asia Pacific, Mr. Chen Zhisheng, Executive Vice Mayor of Dongcheng District, Mr. Joanna Roper, Minister of the United Kingdom, and the Acting Director of the United Kingdom Department of International Trade and Commerce (DFIT) for China, among other distinguished guests. «Picasso’s Muses and Myths» began with Picasso’s oil painting Portrait of Reina, created at the age of 18, and continues with The Man Smoking a Pipe, created at the age of 87, showcasing the artist’s works from different periods and characteristics throughout his 70-year career. The selection of Picasso for Christie’s Beijing inaugural exhibition was significant, as Kenneth Pang, Christie’s Global President, said: «We are honoring this outstanding artistic genius of the 20th century by presenting you with a wonderful Picasso exhibition. His influence was instrumental in the development of the entire art world in the 20th century and beyond.» The exhibition also explores the connections and mutual influences between Picasso and the masters of modern Chinese art. Although Picasso’s works do not bear the direct imprint of Chinese art, he was always curious about Eastern culture and painting traditions, having studied the style of Qi Baishi in particular, and interacting with Zhang Daqian, while Lin Fengmian’s series of «Opera Figures» was heavily influenced by Picasso’s Cubism. Highlights of the exhibition included Picasso’s Bust of a Woman from 1938 and Head of a Woman from 1943, both portraits of his lover and muse Dora Maar. The six works will be offered at Christie’s New York Impressionist and Modernist Evening Sale on November 16th. Christie’s opening advertisement for its new location in Beijing with an authentic Picasso was very effective, making a name for itself in the Chinese art collecting world in just one instance, which shows what power the name Picasso possesses in the land of China today.

A different case was the Picasso Plate Art Exhibition held in Shenzhen in 2017, where a series of 40 prints, including The Triangular Hat and Natural History, were exhibited at Shenzhen Vientiane Art Space from March 11 – May 21, exploring his experiments with lines and literary associations . This exhibition was the first attempt to combine commercial real estate and art lures in Shenzhen. In any case, Picasso has remained a great asset in the Chinese exhibition market, as he had produced an immense array of all sorts of works and only another famous Spanish artist can be comparable for such prolific productivity: Dalí. These two Spaniards were rivals in many ways, but their names together form a top pair. For example, the 2017 exhibition Picasso and Dalí in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, organized by the Chengdu Ocean Pacific Place and an umbrella of sponsors, covered an area of 2,000 square meters in the upper and lower two floors displaying works by the two artists separately. More than 200 pieces by Picasso and Dali’s authentic artworks were on display, including sculptures, ceramics, limited edition signed prints, life images, out-of-print posters and so on. Picasso’s autographed hand-painted pottery and self-portrait series of limited edition prints, were paired with Dali’s sculptures and 200-odd pieces of his ceramics, panel paintings and sculptures; but their classic fine art paintings were not on display. Again, the ticket price was 120 yuan; however, this exhibition was not false propaganda, as the organizer truthfully informed providing accurate details.

Beijing in 2019 welcomed another epic Picasso exhibition: «Picasso: The Birth of a Genius» in the framework of cultural exchanges between China and France, when French President Emmanuel Macron led a campaign for increasing cooperation between the two countries.[25] The show was organized at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in Beijing, an important institution for modern and contemporary art in China, which is located in the core area of Beijing’s 798 Art District and occupies an area of 10,000 square meters, and whose main hall was upgraded by the OMA Design Company in 2019, preserving traces of its industrial history and at the same time having the function of displaying modern art, which ushered in its debut after the upgrading of its venue. Curated by Emilia Philippe, Director of Collections at the Musée National Picasso in Paris, the exhibition was designed for Chinese audiences, offering a comprehensive review of Picasso’s artistic evolution in the first 30 years of his creative career. A total of 103 authentic works, including 34 paintings, 14 sculptures and 55 works on paper, covering Picasso’s creative work from 1893 to 1921 were on display. All the exhibits came from the collection of the National Picasso Museum in Paris, including Picasso’s realistic works Sketching Exercises for Classical Sculpture Plaster Portraits created at the age of 13, as well as masterpieces of the blue period, pink period, and Cubism stage, such as and Three People Under a Tree. The show attracted 350,000 visitors –a historic record in the 12 years of UCCA’s existence– attaining one day up to 9,361 visitors.[26]

In addition to these large museums, more modest institutions are also emerging such as the Meet You Museum, founded in 2017 by the Beijing Zhongchuang Culture and Tourism Industry Group. The establishment is positioned as a mid-range culture and art brand, creating a cultural and tourism landmark in the mode of «museum and tourist attraction». This museum has keenly formulated two thematic routes, one of which is the exhibition of authentic artworks by Picasso and Monet, while on the other hand exploiting the theme of ancient cultural relics such as Egyptian mummies and the Sanxingdui of Ancient Sichuan in China, with authorization to replicate the relevant cultural products to make profits.

The coronary pneumonia epidemic barely affected the craze for Picasso exhibitions, resumed soon afterwards. In 2022, Meet You Museum opened, in cooperation with the Picasso House Museum in Malaga, with the show “Meet Picasso: The Passion and Eternity of a Genius”, fists in Shanghai and then in Beijing. The exhibition featured 192-202 authentic works by Picasso, covering oil paintings, prints, ceramics, sculptures and other materials. However, the novelty of this exhibition is that the organizer directly set up a creation area in the venue, encouraging students to directly participate in art practice as if learning from the master at close range, which is the first of its kind among the existing Picasso art exhibitions in China, greatly enhancing the audience’s participation and sense of experience. The response was excellent! At the same time, the exhibition was accompanied by art lectures, documentary film screenings and other activities to deepen the audience’s understanding of Picasso’s art, greatly enhancing the popularization of science and educational attributes. With the continuous development and optimization of such exhibitions, Picasso’s popularity and popularity are increasing day by day.[27]

The year 2023 coincided with the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s death, and in order to commemorate it in Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macao Bay Area, «Love’s Multiple Repertoire–Picasso Authentic Works Exhibition» was jointly organized by Zhengga Enterprises Group Limited, Picasso Shanghai Art Center, and Guangzhou Guanqi Art & Culture Development Co. Ltd, with the authorization of Picasso Family Members Foundation. First of all «Love’s Polyphony – Picasso’s Authentic Works Exhibition» was grandly opened at Guanqi Art Museum of Guangzhou Zhenggai Art Plaza. The exhibition was divided into 9 thematic units, with 3 oil paintings by Picasso, 20 Picasso prints, 1 Picasso glass painting, and more than 30 Picasso commemorative stamps plus Picasso reproductions. The exhibition lasted until January 3, 2014 before closing and was widely acclaimed by the local people. But then the Jiangsu Province also launched the Pablo Picasso 2023 Asia Touring Art Exhibition – ‘The One and Only Picasso’ Asia’s first exhibition, authorized by Picasso Foundation, supported by the Propaganda Department of Wuxi Municipal Party Committee, Wuxi Municipal Bureau of Culture, Radio, Television and Tourism, Wuxi Liangxi District People’s Government, and organized by Wuxi City Construction Development Group: a total of 50 pieces of Picasso’s authentic works were on display, including ceramics, prints, photography and other form. This exhibition combined academic and technological novelties together, restoring «owl’s eye» Picasso’s ceramics as a main production. Based on the experience accumulated and the model created by the Meet You Museum, the second floor of the exhibition hall was set up with a creative experience area of «Everyone is a Picasso», which provided a rich variety of multimedia displays and interactive experiences, allowing the audience to gain a different sensory experience in artistic interaction and practice. Meanwhile, «Endless Creativity – Picasso’s Artistic Career Retrospective» organized by Kunming City, Yunnan Province, was officially displayed on July 13 at the Yunnan Provincial Museum. The exhibition gathered 152 pieces of works spanning all stages of Picasso’s creative career and various media, including 2 genuine oil paintings, 2 genuine pencil drawings, 19 autographed prints, 1 set of 23 pieces of Picasso-designed limited edition silverware and 12 pieces of Picasso-designed ceramics. This has been the largest exhibition of western artists’ works in Yunnan.

Moreover, the frequency of Picasso’s art exhibitions in China is gradually increasing, and they are not limited to mega metropolises such as Beijing and Shanghai, but gradually begin to spread in more provinces and regions. For example, the “Picasso Imagination Workshop Art Exhibition” was held in Changchun, Jilin Province, Northeast China, from July 13 to October 15, 2024, hosted by Qingze Jiye (Shanghai) Culture and Art Development Co., Ltd. at the exhibition hall on the first floor of Changchun Wanxiang City.[28] More than 50 works were displayed, including 10 authentic Picasso prints and manuscripts flown in from Milan, Italy, some of which were exhibited for the first time in China. The exhibition covered prints, manuscripts and reproductions of Picasso’s works at different stages of his career. The exhibition was more oriented to children and students, focusing on interactive experience with a variety of immersive installations: abstract space created by three-dimensional decorations, body reorganization Rubik’s Cube, and romantic corners in Spanish and French styles. At the same time, art workshops were also set up, such as parent-child painting areas, lacquer fan making, and Picasso exclusive seal playing cards. Singularly, the exhibition adopted a 3D interactive device integrating light and shadow with technology to enhance the sense of participation of children.

Of course, Shanghai and Beijing are still the main markets for this kind of art exhibition. A gardened villa in the Jing’an district of Shanghai has become a specialized Picasso Art Museum, an immersive experience opened in 2024, including 8 thematic units and immersive light and shadow interactive experience. Similarly, “Picasso, Modigliani and Modern Art» opened in Shanghai from September 2024 to February 2025 at the Shanghai Dongyi Art Museum, in collaboration with the Lille Museum of Modern Art (LaM), featuring 61 pieces of works by Picasso, Modigliani, and 18 other artists. In different cities, during the present year 2025 alone they are at least five confirmed exhibitions starring works by him: First the Xiamen Picasso Imagination Workshop exhibition at the L7 Art Center – Xiamen Panji Center, with eight thematic zones covering all periods of Picasso’s creations, including manuscripts, prints and three-dimensional installations. Secondly “Ties that Bind the World: A Century of Chinese and French Masters», until at the Taiyuan Art Museum, Shanxi Province, in cooperation with the Sino-French art exchange program, with the participation of the Museum of Modern Art in Lille, France, which lent some of its exhibits, including masterworks by Picasso. Third is the “Picasso Exhibition” at M+ Museum, Hong Kong, with more than 60 classic works of Picasso on display, covering paintings, sculpture, etc. Fourth, the «Re-encountering Picasso» exhibition of authentic artifacts at Xi’an Qujiang Museum of Art, showcasing 51 signed Picasso works, including rare silver plates. Fifth the “Eternal Temperature: Selected Works of Mr. and Mrs. Ludwig in the Collection of National Art Museum of China», at the White Goose Pool New Venue, Guangdong Museum of Art, with iconic works by Picasso such as Man Smoking a Pipe or Infantryman with a Bird.

Thus, the Picasso craze is not an occasional phenomenon in China, a country very proud of national culture, where such popularity is unprecedented for any foreign artist. Such a position in our show business cannot be separated from the value of Picasso’s works in the art marked, but it is also due to the perceived mutual influence between Picasso as pioneer of modern European avantgardes and his openness towards non-Western cultures. In fact, the second most popular foreign artist in China seems to be Van Gogh, probably for similar reasons…

[1] Wang Shiru edited Cai Yuanpei’s Diary, where it was recorded In 1921 that he had visited with his friend Xu Zhimo their colleague Ferrai (a New School painter). Picasso’s oil paintings hung in Ferrai’s house, and Cai Yuanpei wrote this description after viewing them, expressing his understanding of the beauty of lines in Cubist paintings.

[2] A History of Western Art, published by Lü Lei in 1922 by the Commercial Press, Shanghai, chapter on the Cubists

[3] Salomon Reinach Apollo : histoire générale des arts plastiques, professée à l’Ecole du Louvre. Paris: Picard, 1904 (reedited repeatedly by Hachette since 1905 and also in many other languages). It is worth mentioning that Reinach’s handbook was soon published by the Commercial Press in Shanghai, a publisher that has been instrumental in the translation of Western art into China.

[4] In his lecture Picasso and Modern Painting in 1948, Lin Fengmian mentioned this content. Lin Fengmian passed away in 1991. He served as a member of the National Committee of the Chinese Federation of Literary and Art Circles, a council member of the Chinese Artists Association, and the chairman of the Shanghai Branch of the Chinese Artists Association. This information is recorded in his biography.

[5] China News Picasso joins the party.Published on November 4, 2011, in the Culture Column of China News Network, by Li Jing.

[6] Xinhua Daily, February 4, 1945 edition, February 5, 1945 edition

[7] 1945 Celebration of Painter Picasso’s Joining the Communist Party published in Liberation Daily

[8] People’s Daily Online, «Picasso Once Gave Mao an Oil Painting Destroyed in the April 8 Air Crash» (2014), describes in detail Deng Fa’s meeting with Picasso, the entrustment of the oil painting, and the air crash. People’s Political Consultative Conference website, «Picasso Once Gave Chairman Mao an Oil Painting» (2016), adds the background of Deng Fa’s participation in the meeting and the details of the loss of the painting.

[9] Du Jitang confessed on his deathbed in 2006, admitting that he had been instructed by Dai, as an agent leader of the Junta’s China-US Technical Cooperation Institute, to plan the air crash, which was caused by placing magnets to interfere with the plane’s instrumentation

[10] The French Communist Party specifically commissioned Picasso to create a portrait of Stalin. This request was contacted by Louis Aragon, an important figure in the French Communist Party. The book Stalin: A Biography was published in 2014 by Chinese Language Publishing House. The author is Robert Seewitz (English). The fourth volume of Soviet History, published by China People’s Publishing House, The Formation of the Stalin Model, is one of the key publications of China’s 11th Five-Year Plan.

[11] Xinhua News Agency published a feature article on September 23, 2009, 粉碎四人帮(Smashing the Gang of Four),in Chinese Government Website New China Archives.

[12] New China Archives on China.gov.cn; Ten Years of the Cultural Revolution. Published on June 24, 2005

[13] People’s Daily, July 9, 1972 edition

[14] Zhang Jian, A History of Modern Western Art (The latest reedition came out in 2009, where the chapter on Cubism is in pp. 94-98).

[15] Li Zehou’s The Course of Beauty (1981) explores the inner logic of Chinese art and culture, including an analysis of the relationship between the sprout of capitalism and art. A History of Modern Chinese Thought (1987) puts forward theories such as «salvation overrides enlightenment» and deals with the influence of capitalist culture in the process of modernization.

[16] People’s Daily, Mitterrand’s three visits to China in three capacities.People’s Daily Online, October 9, 2021.

[17] PPCN Forever Young Picasso.Published in Guangming Daily on July 15, 2019, by reporter Tian Ni.

[18] Column in Fine Arts magazine, 1983.It is an academic journal supervised by the Chinese Federation of Literary and Art Circles and hosted by the Chinese Artists Association.

[19] In 1987, Huang Yongping put copies of the Chinese translations of A Brief History of Chinese Painting and A Brief History of Modern Painting in a washing machine and agitated them for a few moments, fishing out the pulp and placing it on a worn wooden box.

[20] Gao Minglu has participated in a number of contemporary art forums to discuss the positioning of Chinese art in the context of globalization. Gao Minglu’s Yi School Theory emphasizes the need for Chinese art to break through the theoretical framework of Western reproduction and construct local narratives.

[21] This audio lecture is presented by Wang Duanting, a scholar of Western art history, and is part of the Shanghai Library’s «Shangtu Lectures – Celebrity Lecture Collection» series.

[22] Xinhua Authoritative Express|Innovative High http://www.news.cn/politics/20240518/9c17264089b941d0a7e265718938d394/c.html

[23] Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the People’s Republic of China, Picasso Great Exhibition https://www.mct.gov.cn/preview/special/13thartsbird/2277/201110/t20111009_131671.html

[24] People’s Daily, Questioning the 2015 Picasso Exhibition http://culture.people.com.cn/n1/2016/0708/c1013-28535170.html

[25] UCCA Center for Contemporary Art, Picasso The Birth of a Genius https://ucca.org.cn/exhibition/picasso-birth-of-a-genius/

[26] The exhibition was described by UCCA director Tian Fayu as a project that «realizes a dream of many years». It was evaluated as «the largest and most academic Picasso exhibition in China so far by Surfing News, Beijing Tourism Network, etc Beijing Tourism, Special Report on UCCA Picasso Exhibition.

[27] Special Report of the People’s Government of Jing’an District, Shanghai,2020-07

[28] Jilin Daily, China Daily, Phoenix and other mainstream media reported on the exhibition, emphasizing its educational significance and innovative form. China Jilin, Picasso’s Imagination Factory on display.